This is the first part of a 3 part review/summary of Kenneth Pollack’s Armies of Sand. To quote Sir Humphrey, I will release the 2nd and 3rd parts, ‘‘in the fullness of time.’’. However, I needed to get this first one out of my system because the glazed look that seems to now descend over my friend’s eyes every time I bring this topic up lets me know I am becoming insufferable.

Armies of Sand by Kenneth Pollack is a book about why Arab armies have historically (post ‘45) performed so poorly. The answer Pollack puts forward is quite compelling because in attempting to understand and predict contemporary Middle Eastern military events I have found his conceptual framework useful. Anyone who has even a cursory appreciation of Middle Eastern history from the end of the Second World War to the present must have been puzzled by this dismal record.

Pollack surveys and puts to the test the four major theories that have been advanced to explain this puzzling pattern. These theories include a reliance on Soviet military doctrine, the politicization of Arab armies, the underdevelopment of Arab economies, and the dominant cultural pattern in the Arab world.

Before getting into the proposed causal factors Pollack sets everything up by focusing on the debacle (from the Arab perspective) that was the Six-Day War. This allows us to get a sense of the major flaws in Arab armies.

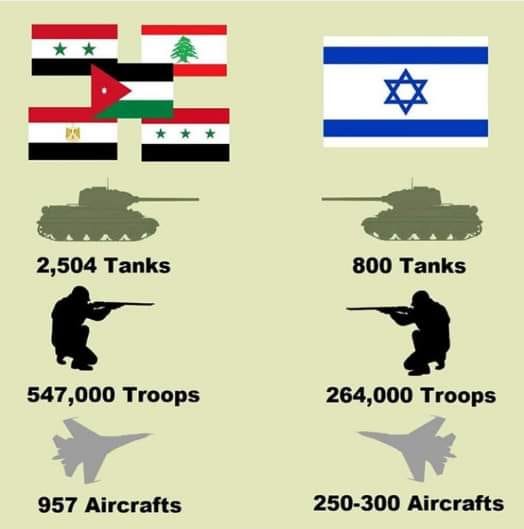

This was a war the Arab coalition should have easily won. Israel was facing Egypt, Syria, and Jordan, with Iraq and Lebanon playing a minor role. Israel’s geography (no strategic depth) and the firepower and men the Arab coalition could put into the field should have made this a foregone conclusion. Just compare these numbers:

Yet despite this overwhelming advantage, the Arabs were trounced in a mere six days of fighting. The defeat was so total that Gamal Abdul Nasser, president of Egypt and the undisputed leader of the Pan-Arab movement, resigned from office (protests all over Egypt in response to his resignation would quickly propel him back into office). The result stunned the world. The Israelis had demonstrated a mastery of modern warfare so complete that their neighbors would cease to seriously believe they could be vanquished. After this defeat, Egypt, under Sadat, would pragmatically moderate its aim to the more attainable goal of retaking the Sinai.

I will briefly sketch out what happened:

On June 5th the Israeli Armed Forces (IAF) used their entire squadron on a single tactical mission (in his book Eighteen Days in October Uri Kaufmann tells us that this was the first and only time such a hair-brained scheme has ever been planned and executed) to destroy the entire Egyptian Air Force (EAF). The IAF hit 18 Egyptian air bases, destroying runways, 298 of Cairo's 420 aircraft, and 100 of their 350 fighter pilots.

By midday Egypt no longer had an air force.

Egypt's senior air officers responded by lying their pants off. Nasser, fooled, conveyed the idea that Egypt was winning to the Syrians and Jordanians. They sent in their Air Force.

Israel lay open as the IAF was finishing off the last remnants of the EAF, yet the Syrians were disorganized and hit nothing of importance. As the IAF returned the Syrians were repulsed, their bases destroyed and their military all but put out of commission. The Jordanians were similarly dispatched.

Pathetically, the Iraqi Air Force could locate neither Tel Aviv nor Ramat David airbase and so decided to attack some random farmland. The IAF made short work of them.

As the air battle unfolded Israel threw 11 brigades into the Sinai. The Egyptians had 7 divisions and 8 brigades in an elastic defense, Soviet-style. They enjoyed the geographical advantage, with the terrain funneling the Israelis along 3 fortified routes. It should not have been one-sided.

In only a few hours the Israelis broke through Egyptian lines. By the 6th, through deft tank maneuvering and deploying paratroopers, the central Sinai had been taken and Egyptian formations enveloped. Seeing this, the shocked Egyptian high command, in desperation, sent in their elite 4th Armoured Division; it too, was similarly crushed.

General Amer, unmanned by this catastrophe, ordered a general retreat without providing a plan for a disciplined withdrawal. A rout ensued as the remaining formations fled toward the Canal.

The Israelis sent their tanks to cut off escape routes for the Egyptians, so the IAF and ground forces could finish them off. This shouldn't have worked as the Egyptians could converge on these choke points with a superior number of troops and armor.

Pollack has a passage that illustrates just how ridiculous this was:

‘‘Some Egyptian units tried to fight their way past what were initially very small Israeli blocking forces at the various passes, but without much success. For example, for most of the day on June 7th there were only nine Israeli tanks (four of them without any fuel) holding the Mitla pass against the bulk of three Egyptian divisions trying to escape to the Canal. Given this absurd force imbalance, it would be an understatement to say that the Egyptians fought poorly. At the Mitla and elsewhere, the Egyptians mostly did not maneuver or counterattack at all but just kept pressing forward, occasionally trying to drive the Israelis off with inaccurate tank fire. In those rare instances when the Egyptians launched a determined attack against an Israeli blocking force, in every case it was a clumsy, slow-moving frontal assault that the Israelis had little trouble dispatching with a few deft maneuvers and deadly long-range gunnery. Moreover, the Egyptian attacks were conducted only with armor—no effort was made to have infantry engage what were often unsupported Israeli tanks and hit them with antitank weapons. Similarly, the Egyptians directed very little artillery fire against the Israeli blocking forces, and the few barrages they did conduct were inaccurate and caused almost no damage.”

Eventually, most units surrendered, while a few stragglers fled on foot (dying in the coming days or in time, captured).

From the beginning of this campaign, the Egyptians fought poorly. On the 5th, as the Israelis broke through their lines they lied right up the chain of command, claiming they were winning and when this became untenable, they grossly exaggerated Israeli numbers, claiming a veritable tidal wave of Israeli soldiers.

They did not counterattack. They did not flank. They did not reinforce. Their artillery accuracy was poor. They seemed allergic to manoeuvre. Their tactical commanders acted like men who had never heard of combined arms operations. All they seemed to understand was the frontal assault (and at a snail's pace at that). Courageous yes, but in an age of mechanized warfare, suicidal.

The pattern of performance of the Egyptian troops would be mirrored almost exactly in the Jordanian and Syrian front. However, I should add, that Jordan’s high command conducted itself with admirable professionalism, and one of the army's tactical commanders, Rakan al-Jazi, showed himself to be a commander of ability. Yet it remains true that their army put in a performance more similar to the Egyptians than not.

The Six-Day War revealed many of the infirmities of Arab armies. More importantly, it revealed those elements of war-making that the majority of Arab armies have continued to perform poorly in, but to understand the persistent failings of Arab armies it is not enough to simply point out their poor record. We must isolate the discrete elements of war-making and determine where they have excelled and where they have failed; moreover, it is crucial to establish whether some Arab armies have improved along one or more of these measures and if so, what has been the cause of that improvement.

To that end, Pollack uses 9 criteria to evaluate the military performance of Arab armies:

1. Tactical Leadership:

Pollack’s verdict is devastating

“Without question, the greatest, most consistent, and most persistent problem of Arab armed forces in battle since 1945 has been the poor performance of their junior officers. From war to war and country to country, Arab tactical commanders regularly failed to demonstrate initiative, flexibility, creativity, independence of thought, an understanding of combined arms integration, or an appreciation for the benefits of maneuver in battle. These failings resulted in a dearth of aggressiveness, responsiveness, speed, movement, intelligence gathering, and adaptability in Arab tactical formations that proved crippling in every war they fought.”

This seems harsh, but when you actually look into the tactical performance, battle by battle, paying close attention to each firefight, dogfight, artillery engagement, and maneuver, it is scandalous how atrocious the tactical commanders are. This is in conjunction with the great bravery of the average Arab soldier. Arab soldiers generally demonstrate great gallantry, but this is often wasted by unit commanders that fail to shift their lines in reaction to a flanking maneuver or penetration of their lines.

On the offensive Arab armies almost invariably go for a frontal assault, eschewing any attempt to manoeuvre along an enemy's flank. On the rare occasions, they do try to maneuver, the attempts are lackluster, bungling, and fail to integrate the different operational units necessary in dynamic warfare.

2. Information Management and Intelligence:

I came to this book with a vague idea about the fog of war - my first association being the Robert McNamara documentary - however, the extent to which Arab forces suffer from this dynamic and the self-inflicted nature of its outsized impact on them has floored me.

Pollack notes:

“It has been the history of Arab armed forces that personnel throughout the military consistently exaggerated and even falsified reporting to higher echelons. Simultaneously, superior officers routinely withheld information about operations from their subordinates. These reinforcing tendencies meant that Arab militaries routinely operated in a thick fog of ignorance and half-truths. The lying and obfuscation that enveloped the Egyptian armed forces during the Six-Day War is simply the most famous example of this persistent problem. Lower echelons sent inaccurate reports to higher echelons, who then made plans based on this misinformation. Since the higher echelons rarely provided all available information to lower formations, many units had to execute operations with little knowledge of the enemy, the terrain, or the larger mission. The lower echelons then either had to try to execute the operation—which may have been suicidal because of the limited and inaccurate information available to the planners—or lie and report that they did perform it when they had not.”

The withholding of information is a particular attribute of bureaucracies and though regrettable is to be expected. A national Army is a bureaucracy, indeed one might even say the queen of bureaucracies, yet even so, allowing for a certain caginess in the horizontal flow of information, the vertical flow is always sacrosanct. Armies rely on their ground troops conveying factual information up through the chain of command. The resulting chaos from a failure to uphold this fundamental rule is tragically predictable.

As if this was not enough Arab intelligence services and generals have, in the past, consistently failed to seek out and collate publicly available information on the enemy. Instead, information has often been distorted to fit prevailing biases and expectations. To what extent this has changed remains to be seen.

This has often proven doubly catastrophic because field commanders often failed to patrol consistently and aggressively. Reconnaissance by the Air Forces has consistently been inadequate and disorganized. The field commanders usually prefer to rely on information relaid from the top. This means

“Arab armies often went into battle with little understanding of the order of battle, organization, infrastructure, plans, or tactical doctrine of their enemy.”

Jeez.

3. Technical Skills and Weapons Handling:

Arab armies have often been outfitted with the latest military equipment, at certain periods purchased from the Soviets or the West, yet they have consistently failed to utilize the full range of the equipment’s capabilities. They use the latest tanks like a battering ram or an RPG.

I am reminded of nothing so much as Zlatan Ibrahimovic noting, in his inimitable way, that the way Pep Guardiola was using him was like ‘using a Ferrari like a fiat.’

In fact, one of the factors that has led to Arab Air Forces doing poorly has been their abysmal use of the latest in fighter jet technology. The latest MiGs and Mirages have fostered no serious improvements because the pilots have rarely gotten to grips with the technology that makes one generation of fighter jet superior to the previous one. Not only that, the rate at which they've been able to train adequate pilots or specialists to pilot their aircraft or operate their tanks is such that they are often unable to field the full complement of their aircraft and tanks.

Pollack makes an illustrative point:

“Arab air forces were rarely able to sustain even a 1:1 pilot-to-aircraft ratio, and there were numerous examples of worse ratios. For instance, the Egyptian Air Force in 1956 had only 30 pilots for its 120 MiGs, a 1:4 ratio. Libya had only 25 trained pilots for its 110 Mirages in 1973, and four years later had only 150 pilots for the 550 aircraft in its air force. Indeed, after the 1967 Six-Day War, the Egyptians essentially accepted that it was impossible for them to train more than about 30 pilots a year, despite a population of 30 million people. These problems were not confined to Arab air forces either: the Libyans were never able to train crews for more than about a third of the tanks in their arsenal, while the Syrians had trained crews for only two-thirds of their armored vehicles before civil war broke out in 2012.”

4. Strategic Leadership:

This is where things get interesting because Arab armies have produced some excellent generals. Zaid Bin Shakir of Jordan is one example. His planning and execution of the campaign against the fedayeen after the initial setbacks was nothing short of excellent. He made sure the army learned from the mistakes it had made in that initial campaign and brought professionalism and effectiveness to the war-making capabilities of the army. This is all the more surprising because he was, in large part, advanced for his political loyalties to the king. So even the highly politicised Arab armies have produced excellent generals. Men like Ali Aslan (Syria), Hezbollah’s 2006 war with Israel, and Da’esh’s generals in their 2014 invasion of Iraq are further examples of this.

However, some of the generalship in Arab armies has varied wildly over time. The Egyptian army’s generalship under Amer was terrible, but in ‘73 was almost faultless - Egyptian high command during this war (General Saad Shazly deserves a particular mention as it was his plan that succeeded and more than any other member of the high command he understood the nature and limits of Egypt's victory in those early days) was superb; Iraq’s army from 1980 - 1986 was criminally incompetent, but a revamped Iraqi general staffs planning in the 1987/1988 campaign was brilliant.

That being said, the quality of Arab generalship is very much dependent on the level of politicization of the army under consideration, but even highly politicized armies, when certain conditions have been met, as the Jordanian and Syrian cases demonstrate, can produce a competent high command.

5. Unit Cohesion:

The U.S. Army Field Manual FM 6-22 Developing Leaders defines cohesion as “the unity or togetherness across team members and forms from mutual trust, cooperation, and confidence.”. Basically, it's the strength of a unit's bond and how that bond sustains them in difficulty and aids them in pursuit of their goal. Think of the Sir Alex Ferguson Man U teams in ‘Fergie time’ as a demonstration of high unit cohesion or even the steadfastness, discipline, and unity of purpose the Fremen demonstrate in the face of Harkonnen counterinsurgency tactics.

Arab armies have usually done well in that respect. Certainly, there have been times when units have dissolved rapidly, however, these moments have been rare and usually (though not always) explicable given the factors at play - the most important being an order to conduct a general retreat without a proper plan (remember Amer).

This generally strong unit cohesion has at times risen to positively heroic levels. Pollack has a lovely passage about this:

“The most prevalent pattern has been for Arab tactical formations to remain cohesive and combat effective even when placed in dire situations in which it would have been reasonable to expect the forces of any army to dissolve. Hizballah’s tenacious defense of South Lebanon against the IDF in 2006; the stand of the Iraqi Republican Guard during Operation Desert Storm in 1991; the repeated attacks by Iraqi armor against more competent Israeli defenders during the October War of 1973; the Egyptian defense of Abu Ageilah and Umm Qatef in 1956, and again in 1967; the Jordanian defenders of Ammunition Hill and many other positions around Jerusalem in 1967; the tenacious Syrian defense of the Bekaa Valley in 1982; and the determination of Libyan units to hang on in the Tibesti region of northern Chad in 1987, all attest to superb cohesion by Arab formations under extremely adverse conditions. Likewise, while they are slightly different situations, the ability of Houthi forces to mount repeated offensives against the Yemeni government since 2010, their ability to hang on in the face of a far better armed and supplied Saudi-Emirati counteroffensive after 2015, and the stubborn Da’ish defense of various Iraqi and Syrian cities from Ramadi to Raqqa in 2015–2017 attest to similarly impressive cohesiveness.”

6. Logistics and Maintenance:

On the whole Arab militaries have had good logistics, with quartermasters at times demonstrating an enviable creativity and finesse despite a rigid and cumbersome logistical system. The Iraqis were able to supply an army of a million men for over 8 years during the war with Iran and they also moved and supplied half a million men in their invasion of Kuwait. The Libyans, despite their military support infrastructure being thousands of miles away, supplied, moved, and sustained their armies in Chad and Uganda.

These accomplishments have generally been the rule amongst Arab armies, with Syria being the stand-out exception.

Interestingly, this record among the Iraqi forces held until the fall of Saddam. Why this is the case Pollack does not seem to know. He does point to the venality of the Iraqi army, its transition from the paper tracking system to the American-favoured computerized system, and the army’s need to import Western contractors to handle the more sophisticated weapons like the M1 tank and F-16 fighters. However he seems to acknowledge the incompleteness of this picture, after all, the Iraqi army was not exactly free of corruption under Saddam and while the Iraqis seem not to like the new computerized system, people tend to adapt, why the Iraqis haven't is puzzling.

Perhaps I'm too optimistic about the ‘people tend to adapt’ part because one thing Arab forces haven't adapted to, is the need to maintain their equipment. Usually, logistics and maintenance go together, but Arab militaries have certainly done their best to draw a sharp divide between the two. Pollack has this to say:

“Most of the Arab armed forces had a poor track record of keeping their weapons, vehicles, and other equipment up and running. Most Arab soldiers and officers showed little appreciation for the need to attend to their equipment, with the result that units generally had operational readiness (O/R) rates of only 50–67 percent. O/R rates greater than 70–80 percent were rare among Arab units, while rates as low as 25–30 percent were not. Combat units had too few personnel capable of repair work, requiring them to perform even the most minor repairs at large central depots. In addition, the personnel manning these repair depots were often foreigners.”

He does however add that the Jordanian army does a better job.

7. Morale:

Morale in Arab armies, as most would expect, has risen and fallen depending on the war, time, and effectiveness of the particular army under consideration. The Egyptian soldiers’ morale was incredibly high in ‘67, the Arab coalition soldiers’ morale was high in ‘48, the Syrian and Egyptian soldiers were champing at the bit in ‘73, and Da’esh’s battalions in 2014 were all but incandescent with their commitment. There are other such examples. Conversely, there have also been times when the soldiers wished for anything but combat. The Iraqis in Desert Storm and the Second Gulf War are a case in point.

This morale, though it contributed to the performance of the different forces, has not been the decisive factor in the effectiveness of the armies. The Arab coalition was defeated in ‘48, the Iraqi Republican Guard gave a good accounting of themselves in Desert Storm, and high Egyptian morale at the commencement of hostilities in ‘67 counted for nothing. All this seems to suggest morale is not the main factor in Arab military fortunes.

Pollack adds an interesting postscript to his analysis of the morale in Arab armies:

“officer-enlisted problems do not appear to have been as bothersome to the Arabs as was once widely believed. Problems between officers and their men have their greatest impact on morale, discipline, and unit cohesion. Yet Arab armies that suffered from officer-enlisted problems did not always suffer from morale, discipline, or unit cohesion problems. Moreover, even in those cases where both were present, it was not always the case that the one was the product of the other. For example, for 20 years before the Six-Day War, Syrian officers had paid little attention to their men, considering the preparation of their units for combat irrelevant to their professional ambitions. Many of them fled when they realized the Israelis had flanked the entire Syrian defensive system. However, Syrian tactical formations showed no lack of commitment, discipline, or cohesiveness. Although there were some Syrian units that melted away even before Israeli forces came near them, far more stayed in place and fought hard even when their positions were hopeless and their officers had abandoned them. This is not to suggest that poor officer-enlisted relations were not harmful, only that the harm appears to have been less than has often been claimed. Like poor morale more generally, Arab armies have suffered from having poor officer-enlisted relations at times, but have not suffered excessively from it. It never proved the difference between victory or defeat.”

For me, this highlights the importance of epistemic humility. While friction between the officers and enlisted men should in theory and often does in practice harm morale, unit cohesion, and discipline, it is important to go study the campaigns, unit by unit, and see if this continues to hold true and whether it is the decisive factor in victory or defeat.

8. Training:

Arab armies - with the exception of the Jordanians, who have always taken training seriously - only really started training seriously after ‘67. This is of course excepting the Libyans, who have never much bothered with training.

After ‘67 Egypt and Syria's armies trained consistently and rigorously. Indeed, for the Yom Kippur War, the Egyptian army practiced the Suez Canal assault 35 times, and units practiced and trained for their specific roles hundreds of times.

Middle Eastern experts have sometimes ascribed these poor training habits to the use of the army as an internal security force. This explanation does get at something true because armies geared toward internal security do not require the same training as a conventional military and are therefore likely to fare poorly when faced with conventional military operations.

This falls apart somewhat though when you look at the Iraqi Republican Guard. They went from an internal security force to the Iraqi army's elite corps relatively quickly and were vital to the success in the later stages of the war against Iran and the invasion of Kuwait.

Ultimately most Arab armies have moved away from an internal security orientation and have also diligently applied themselves to training, yet they have continued to underperform.

9. Bravery and Cowardice:

I get the sense that the gallantry of Arab soldiers has often been traduced. Pollack is having none of that and I'll have to quote him here extensively, so everyone gets a sense of the man's vehemence:

“Arab military history demonstrates that of all the problems experienced by the Arabs in combat since 1945, a pervasive cowardice has not been among them. It puts the lie to the slanders of those who have dismissed the Arabs as cowardly soldiers. Of course, one can point to any number of incidents in which individual Arab soldiers, officers, or even entire units behaved in a less than valorous manner. However, this is true for every army. Even the Japanese Army of World War II had its share of cowards. The key questions are how widespread was such behavior, was it more prevalent than courageous performances, and how much did acts of cowardice affect Arab fortunes? On each count, the historical evidence demonstrates that Arab armies performed creditably, if not meritoriously. There are countless anecdotal accounts of Arab soldiers and officers sacrificing their own safety for their comrades or their mission, and the opponents of the Arabs generally credited them with staunch (albeit not necessarily skillful) resistance. On the offensive, Arab forces routinely charged into murderous fire and kept up their attacks even when mauled by their adversaries. This pattern was evinced by the Iraqis against the Israelis in southwest Syria in 1973, by the Syrians on the Golan in 1973, by the Syrian Air Force over Lebanon in 1982, by the Libyans at Aouzou in 1987, and by the Saudis at the Battle of Khafji in 1991. Whatever we may think of Da’ish, no one can say that their fighters were not tremendously brave throughout the 2014–2015 offensives. On the defensive, Arab units often fought ferociously from their positions, even long after they had been outflanked, bypassed, or otherwise neutralized. Jordanian defenders on the West Bank in 1967 and at al-Karamah in 1968; Libyan forces in northern Chad in 1987; Egyptian forces in the Fallujah pocket in 1948, at the Mitlah pass and Abu Ageilah in 1956, at Rafah, Khan Yunis, Abu Ageilah, Umm Qatef, and the Jiradi Pass in 1967, and at the Chinese Farm and Ismailia in 1973; Iraqi forces at al-Basrah in 1982 and again in 1987; as well as Syrian forces on the Golan in 1967, and in Lebanon in 1982, all demonstrated tremendous courage in standing their ground and fighting hard in extremely difficult situations. Arab rearguards, when they were employed, usually fought hardest of all, sacrificing themselves to see that the rest of their armies escape safely. Egyptian forces at Jebel Libni and B’ir Gifgafah in the Sinai in 1967, and the stand of the Iraqi Republican Guard against the US VII Corps in 1991 attest to the willingness of Arab rearguards to do their duty even when it meant their destruction. Indeed, what is truly noteworthy about Iraqi performance in the Gulf War is not that 200,000–400,000 deserted or surrendered to coalition ground forces, but that after 39 days of constant air attack, the destruction of their logistical distribution network, their lack of commitment to the cause, and their clear inferiority to Coalition forces, another 100,000–200,000 Iraqi troops actually stood their ground.``

Amazing read!

I have enjoyed it from beginning to end. Definitely recommend it.

It’s an honest discussion and review of Arabs behavior in war, in previous years,/specifically against Israeli forces/ and how it affected them in the past and caused them defeats while they seemed to be the upper hand and how that might impact them in a future war; Discussed, middle Easterners need of a movement towards development and adaptation, because bravery as their best quality is deemed nothing in chaos!

Indeed, When lacking or short of strategy, organization, training and moral bravery stands a fool failing to save the Middle East and win a war against a small force!